Cabo Verde & The Island of Fire

/Our grand plan, assuming a successful Saharan crossing, was to unwind in The Gambia’s warm, palm-fringed embrace. Unfortunately, the reality of Africa’s smallest mainland country didn’t quite match up with our expectations and we were looking for alternatives.

Cabo Verde, a cluster of islands almost visible on the horizon, looked like a smart choice. After making quick arrangements for Bob to wait for us at Sukuta Camp, we caught a short flight from Banjul back to Dakar, and from there, flew directly to Santiago, the largest of the Cape Verdean isles.

Cabo Verde lies just 570km off the African mainland. Ten volcanic islands, born of fire and salt, left unclaimed by humankind until the Portuguese stumbled upon them in the 15th century. Colonised in 1462, the archipelago soon became a maritime crossroads between Africa, Europe and the Americas. Salt, cotton and slaves were processed through the islands, ships were restocked and repaired before continuing west and shelter sought from an often-hostile ocean.

ilheu de santa maria

After five centuries under Portuguese rule, Cabo Verde shook off its colonial chains following the Carnation Revolution in Portugal – a peaceful, bloodless military coup that overthrew the dictatorship in Lisbon and ended colonial wars in Africa. Today, the islands are known more for political calm and far-flung diaspora. Tourism is growing thanks to their beautiful and varied landscapes and despite limited natural resources, a functioning and creative society thrives on the resilience, culture and warmth of its people.

Having declined to visit the older, flatter, islands of Sal, Boa Vista and Maio, renowned for their all-inclusive luxury resorts, we set about exploring Santiago. The capital, Praia is home to over half the nation’s population of 300,000 and is the youngest capital city in Africa, having officially replaced Cidade Velha in 1770. Lacking the polish and glamour provided by modern hotels and shopping malls, the city is a mix of colourful buildings and simple streets. Although a bit rough round the edges, it is the country’s main political and economic centre and offers an unpretentious experience of Cabo Verdean urban life.

Slightly away from reality, we were fortunate enough to have booked into a hotel just metres away from the Ocean overlooking the Ilheu de Santa Maria (Quail Island), an islet that was the first stop of Darwin’s Beagle voyage in 1832. With a history that includes serving as a leper colony and coal dockyard, the islet was recently destined to be turned into a resort and casino by a large Chinese company, but given the only progress over the last eight years has been the construction of a connecting bridge we guessed that life on the islands plodded along at a fairly sedate rhythm.

Despite being warned several times not to wander the streets of Praia at night, we didn’t run into any trouble. Still, we preferred the quieter interior, away from the city’s busy markets and constant noise. The island is shaped by a couple of mountain ranges, deep valleys (ribeiras) and small traditional villages – and it didn’t take long to see the main sights.

asomada markets

The inland hiking through the Serra Malagueta Park and the Pico d’Antonia range would ordinarily have been a highlight but our attempt to summit the island’s highest peak, which at 1,394 metres barely qualifies as a mountain, failed miserably. Likely battling our third round of Covid and unable to climb more than a few metres without having to sit down and catch our breath, we admitted defeat a few hundred metres from the top and went in search of a taxi.

mindelo, sao vicente

More successful was a visit to the colourful Asomada markets and the curved sandy bays of Tarrafal, a scenic trio of beaches on the island’s northern coast.

Praia aside, nothing moves quickly in Cabo Verde and any plans we had of using the ferry system to travel between islands were quickly abandoned after warnings from long-suffering locals about the unreliable service. The aging ferry fleet has apparently been shrinking for years, a decline that was sharply underscored by the tragic sinking of the MV Vicente in 2015. The ship, overloaded and operating in rough seas, went down off the coast of the island of Fogo, resulting in the deaths of 15 people, including crew and passengers. Not surprisingly, given the little or no progress that has since been made in modernising or replacing the fleet, public confidence in the ferry service has remained low and with that in mind we opted instead for a short domestic flight to Sao Vicente.

In contrast to Praia, we found Mindelo – Sao Vicente’s capital – most appealing. There was a lively music scene, some attractive colonial buildings and a stunning bay. We stayed in an old villa on a hill above the harbour, run by an Australian couple who had successfully introduced a fusion of international flavours into the traditional rustic and hearty offerings which resulted in some of the best food we had eaten for many months. We managed some more successful hiking, helped out at the local dog shelter and even managed a quick swim with the giant turtles at Sao Pedro beach before heading on to the next island, Santo Antao.

Santo Antao, often promoted as the hiking capital of Cabo Verde, stands out as one of the few islands without an airport. We did hear rumours that one is in the works but suspect that the project is still some years away. For now, the only option to reach the island is a one-hour ferry from Mindelo. Despite being handed sick bags as we boarded, the crossing was uneventful albeit rather choppy.

Santo Antao is the greenest and most mountainous island of the Cabo Verde islands. Although the second largest in size, it’s home to just 35,000 people, giving it a remote, underdeveloped feel that soon had us more relaxed than either of could recall. The ferry docked in Porto Novo, the main port town where we squeezed into a local alguera which bounced and rattled its way for an hour along the cobbled coastal road before reaching the small fishing village of Ponta do Sol.

porto do sol to cruzinha trail

We didn’t stay too long, just long enough to tackle the spectacular coastal trail from Ponta do Sol to Cruzinha. It’s a point-to-point walk of about 13km, that hugs the dramatic northern coastline. The path itself is paved with centuries old stone and was originally carved into the cliffs providing a way between remote fishing and farming villages that were, and still are, largely inaccessible by road. The trail weaves around crumbling cliff edges, descending into valleys before climbing sharply back up to ridges with panoramic views and passing through a scattering of colourful cliffside villages.

eco lodge, santo antao

Further around the coast we checked into one of the island’s better-known eco lodges. A calm, elevated retreat founded by a Belgian couple; one a photographer, the other a chef. Perched above the ocean with wide views and excellent food, the place had an effortlessly relaxed vibe. Due to popular demand, Chef Guy also offered up his skills as a boatman and one morning dropped us, along with a few other guests, on a remote, rocky stretch of shore a way along the coast. Pointing up at one of the many surrounding mountains he vaguely indicated the way back before departing to catch some fish for dinner.

We would have loved to stay at this accommodation longer, but the lodge was closing for a short break, so we pieced together a four-day walking route across the island’s interior, ending at the Cova Crater. Not having intended nor packed for a multi-day hike and taking into account the high temperatures and mountainous terrain, we were more than a little relieved to arrive at our final destination having resisted the temptation to ditch the laptop, two tablets, a hairdryer and Ian’s inexplicable collection of four pairs of shoes. Accommodation along the way was provided by small local guesthouses, simple, clean and welcoming. The only people we met on the trail were locals, always friendly as they were going about their business which, at the time of our visit, was harvesting the sugar cane required to make the strong traditional distilled grogue.

descent from covo crater

The walk culminated in a long climb out of one of the island’s lush valleys onto the plateau above the crater. A dramatic volcanic caldera, one of Santo Antao’s most iconic natural landmarks. Nearly a kilometre wide, the broad green plain of the basin stretched out below us reminding us just how volcanic these islands really are.

Our final hike on Santo Anto took us from the crater down into the Paul Valley, another popular trail. The path dropped a full thousand metres, winding through pine forests and steep agricultural terraces thick with bananas, papayas, and coffee plants. lt was stunning, though clearly no secret and we passed more hikers on that descent than we’d seen all week. Back on the coast, we retraced our steps; a ferry back to Sao Vicente followed by a short flight to Santiago from where we could catch a connection to take us to Fogo – the island of fire.

That was the plan, anyway. What should have been a 30-minute flight followed by a quick transfer and another short hop turned into a drawn-out odyssey. A three-hour delay made us miss our connection, and we sat around for another two hours before someone rustled up a standby aircraft.

It’s tempting to look at a map of Cabo Verde – all those islands clustered together – and assume that travel between them is easy. It isn’t. Not even close

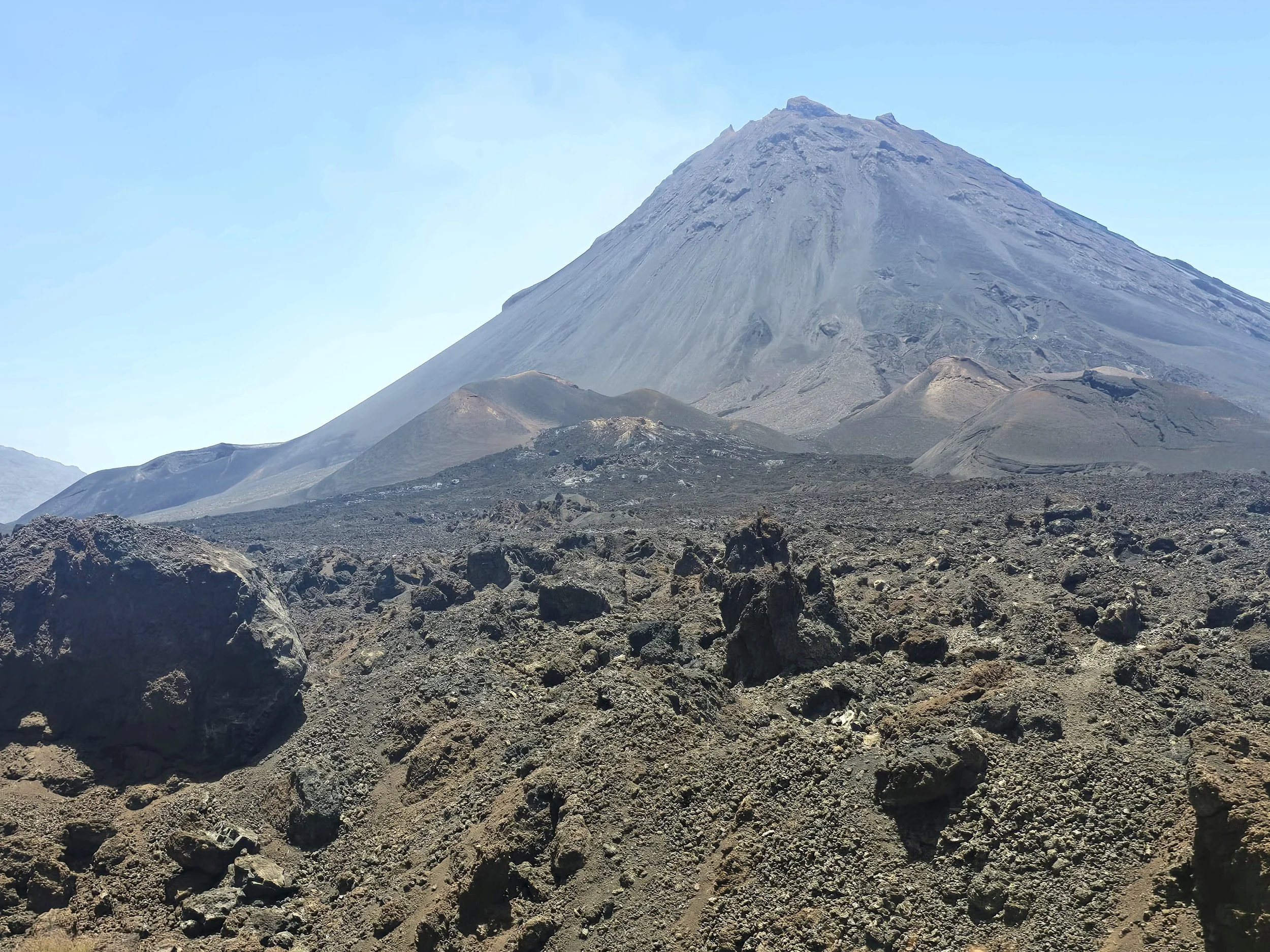

pico do fogo

The island of Fogo, youngest in the archipelago, is a smouldering, strombolian troublemaker that has erupted more than 30 times since records began. Its most recent outburst was in 2014 and the one before that in 1995, a reassuring enough gap to make us feel vaguely optimistic about our timing to climb to the summit. We landed in the island’s main settlement of Sao Filipe, a sleepy colonial-era town perched on the volcano’s western flank. After a couple of nights at yet another peaceful eco lodge overlooking the coast, we made the hour-long drive up to the eerie Cha das Caldeiras – the high-altitude lava plain inside the volcano’s caldera. The landscape here was bleak but strangely beautiful. Eight kilometres of dark volcanic soil, punctured by fumaroles and fissures, with occasional bursts of life in the form of grapevines and improbably cheerful garden plants. Towering another 1,000 metres above us was the central cone of Pico do Fogo, sharp and moody – a brooding reminder that the whole setup could (and eventually will) blow again.

The scene felt like something out of Mad Max, with its sparse dwellings, scorched terrain, and the haunting silence that comes with high-altitude desolation. And yet, people live here – by choice. The homes, many made from lava blocks, are often built directly on top of the remains of earlier houses consumed by lava. Even the road had been freshly re-laid over the 2014 flow, with the previous one now entombed beneath tonnes of black rock.

cha das caldeiras

After sampling the local wine (yes, they grow grapes here and produce some of the island’s best whites), we arranged for a local guide to take us up the volcano. He introduced himself as “Drew”, which didn’t strike us as particularly Cabo Verdean, so we probably misheard. Regardless, he turned out to be excellent – friendly, fluent in English, and fiercely proud of the tight-knit caldera community.

We set off at dawn the next day – earlier than seemed necessary, until we spotted several groups already picking their way up the slope ahead of us. The trail was vague and often disappeared altogether, winding in a zigzag up the northwest flank through ash, lumps of pumice and loose boulders. As we climbed, the gradient increased until two and a half hours later we reached the crater rim, leaving only the final 100 metres to the summit – a daunting, near-vertical scramble up crumbling rock. A steel cable had been bolted into the side, which helped a bit, though it did occur to me that anywhere else, I’d be clipped in with a harness, a helmet and perhaps a strong insurance policy.

on the rim of pico do fogo

There was no grand marker at the top, no cairn, no plaque, not even a weather station. Just a ragged ridge and a lot of wind. But the view, usually lost in cloud, opened briefly for us, revealing the vast, scorched caldera floor far below, still steaming in places. After a short breather, we picked our way across a ridge above the smoking crater and began our descent via another steel-cabled section. This led onto a slope of fine, dusty ash, ankle-deep and sliding with every step. The only logical way down was to run, which we did, laughing, slipping and completely surrendering to gravity. By the time we reached the bottom we were covered in black soot, socks filled with ash, shoes trashed, and Ian sporting a nicely grazed arm as a memento.

In a surprising twist, our flight back to Santiago actually departed on time and after the briefest of layovers, we were back in the air on a satisfyingly larger aircraft, bound once more for the African mainland