GR11 - A Walk in the Mountains

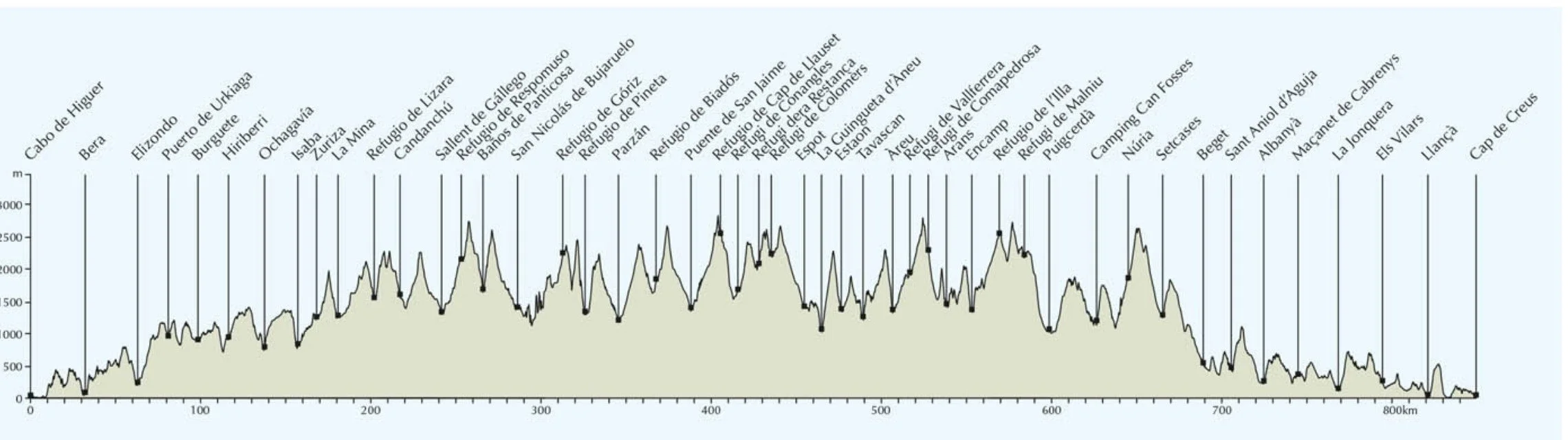

/If one were a straight-flying crow, the distance from one end of the Pyrenees to the other would be a little over 400km, for a long-distance hiker however, an 850km plod is required to get from one side of the mountain chain to the other. From Irun on the Atlantic coast to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean, the navigation of high passes and sweeping valleys demand 39,000m of ascent and descent, the equivalent of climbing five Everests or for those of you in the UK, 40 Snowdons! The Spanish GR11 is one option for this traverse, others include the French GR10 and the Haut Route-Pyrenees (HRP), a high route which zigzags across the Spain/France border. This would be our biggest hiking undertaking to date, one that required full packs including tents, cooking equipment and adequate essentials to keep us on the trail for the eight weeks and one day that it would take for us to complete.

GR11 - atlantic to mediterranean

The Cicerone Press “Trekking the GR11” was to be our guide, presenting the route in 47 stages over 5 sections with the advice that west to east would put the weather at our backs and experience of high mountains would be required.

Assuming adequate fitness levels and appropriate equipment, the hardest element of a trek of this nature is being able to free up enough time. The variety of climates and altitudes make choosing the right season crucial and the trail is probably best walked between late June and September, when the snow has largely melted from the high passes and the weather is more stable. Unlike some of Europe’s more popular long-distance routes, the GR11 somehow remains a little under the radar which rewards with fewer hikers and a closer connection to nature thereby enhancing the sense of adventure that towering peaks and wild landscapes inspire.

For this particular exploit, we were joined by Ian’s twin sister Helena, recently retired, based in Australia and enthusiastic at the idea of a bit of hiking in Europe. Ian had supplied her with a stripped-down list of essential items that would be required for the trip and Helena met us in San Sebastian, a couple of days before we were due to start, struggling under the weight of her fully loaded rucksack. It is always difficult to envisage what an essential item is when far removed from the activity itself and we are probably all guilty of carrying gear that we could have managed without. But, given this was to be Helena’s first time carrying a full pack, let alone a multi-day trek, I have no doubt that she was later grateful that we persuaded her that the white jeans were unlikely to be required.

Our two days in San Sebastian flew by and all too soon we were stood in front of the Cabo Higuer lighthouse looking down at the Atlantic Ocean crashing against the rocks of the headland. We had planned to dip our boots into the ocean, a symbolic start for what lay ahead, but as this would have meant a steep clamber down the cliffs we opted for a selfie instead. It wasn’t until later that we realised our shot hadn’t even been taken beside the GR11 information board, so no solid proof that we made it to the start at all!

The first section, Cabo de Higuer to Zuriza, took us through the green rolling hills of the Basque Country, “a gentle transition from hills to modest mountains” the guidebook said. The Cambridge Dictionary describes the word gentle as calm, kind, or soft, and I think I speak for all of us when I tell you that none of these words came up as we battled through this preliminary stage. Our packs were too heavy, the temperatures were too high (unless it was chucking it down with rain), there was little or no water to be found on the trail and we were walking at a pace that was taking significantly longer than the suggested timeline in our book.

col de zagua

Over the course of this stage our tents made numerous appearances as the alternative was to cover distances of over 30km a day in order to reach accommodation. We were quick to take advantage of proper beds when we did come across them and these were generally provided by rural guesthouses or hostals (small hotels not hostels), which although basic were appreciated more than a 5* hotel under different circumstances. Our waymarkers, white and red stripes, were easy to follow and found on rocks, trees, gate posts and the sides of buildings as we passed through authentic, picturesque villages. Provisions weren’t a problem provided we thought ahead a day or two and notwithstanding a somewhat unvaried diet which mostly consisted of cheese sandwiches, we didn’t go hungry.

navarre, basque country

Part of the enjoyment of undertaking a trail such as this is the opportunity to slowly get to know the area; its people, their customs, the fauna, flora and to meet other hikers on the trail. But, the biggest attraction of the GR11 are the landscapes and there was barely a day when they disappointed. This first section in Navarre, Basque country, offered up green, rolling, bracken-covered hills, beech forests, limestone plateaus and, ever beckoning in the background, the Pyrenean mountains.

Navarre is an autonomous community in northern Spain right on the border with France, famous worldwide for the Running of the Bulls during the San Fermin Festival. The festival, which lasts for 9 days, was taking place in the city of Pamplona as we hiked through the hills above. St Fermin was Pamplona’s first bishop, rumoured to have been dragged to his death due to being tied to a bull by his feet. Whether or not this is true is up for debate but the traditional uniform for all bull runners is red and white. White clothes to represent St Fermin himself and a red scarf or handkerchief to represent the blood from his death. The bull run takes place each morning at 8am, 2-4 minutes of utter madness which is then shown on repeat throughout the day in every bar, café, restaurant and hostal. Six bulls (and six steers to guide them) are released 875m away from the bullring, which is accessed via old, narrow streets. Runners number anywhere between 1,000-4,000 and are required to run at speeds of between 15-24kph over slippery cobblestones if they want to stay in front of the stampeding bulls. It is a free event that anyone can get involved in provided you are over 18 and not under the influence of alcohol. There are large fines if you are seen touching a bull and injuries are commonplace. Being trampled by other runners is rather more likely than being gored or trampled by the bulls and only 16 people have died over the last 100 years!

OK, back to the GR11 …..

ascent to collado de esper

….. The second section, Zuriza to Parzan took us into the High Pyrenees where challenging mountain passes upped the ante and the appearance of via ferrata cables, stapled into the rock face to aid progress, had Helena seriously considering the sanity of continuing. Mountain refugios became havens providing shelter, meals and the opportunity to bond with fellow hikers over blisters, missing toe nails and those mysterious random body pains that start in your left knee and move to your right hip before progressing to both elbows and culminating in you top left molar.

refugio respumosa

There is a huge network of these mountain huts which range from unmanned emergency shelters to modern buildings where, if you are lucky, you can opt for a double room with en-suite rather than a bunk in a dorm for 30. Many of them are found in the most stunning spots, often beside reservoirs and surrounded by towering peaks. Their isolated positions require provisions to be brought in by helicopter; the same helicopters that provide hikers and climbers with a rescue service. We met a French couple who had come across a lone male hiker who had fallen and broken his arm. They called for a rescue on his behalf and did the same again the following day for a lone female hiker that had broken her ankle. In both instances the rescue helicopter turned up within an hour. Unfortunately, they missed the 27-year old American hiker whose body was found a month after he fell 200m down a mountain. But, fortunately for us, we didn’t see this French couple again although our exchange with them did serve as a stark reminder that the mountains don’t care whether you make it across or not.

The spectacular mountain scenery continued as we ascended higher. Water en-route was easy to find and the trail remained relatively straightforward to follow, the red and white stripes often supplemented by cairns. Long, steep ascents were inevitably followed by long steep descents and huge bounder fields slowed our already slow progress even more. The Collado de Tebarray, the most demanding col on the GR11 was highlighted in our book as “not a route for the inexperienced”. We were now over 2 weeks in, how experienced did we need to be??

ordesa canyon

The final days of this section took us through the Parque Nacional de Ordesa y Monte, the jewel in the crown showcasing the magnificent canyons of the Garganta de Bujaruelo the world-renowned Ordesa. After days of isolated hiking we were suddenly surrounded by hordes of day hikers before the GR11 peeled away from the main tourist routes and led us over yet another high col before leading us down 1500m of hideous, steep, rocky descent down to Parzan.

Should you be considering an undertaking such as this, Helena has some savvy advice …..

……. What I Wish I’d Known Before Tackling the GR11 in the Pyrenees

When people say the GR11 is a “great walk for beginners doing their first multi-day hike” what they don’t mean is it’s a great walk for beginners.

This trail is no gentle intro. It’s a rollercoaster of peaks and valleys, and if you walk at a slower pace (like me), odds are you’ll spend the last two hours of the day trudging downhill into a village just in time for the sun to be at its most unforgiving and the roads to be made of lava—or at least they feel like it, with all that heat bouncing off the pavement straight back at you.

how many times can i blame the footwear?

Move slow and you’re just stuck in the furnace longer. The upside is that legs bounce back surprisingly fast. So don’t try to “save energy”—just keep moving, even if your calves are screaming. They’ll forgive you by morning.

One of the smartest things I packed was sunscreen. Even if it added a bit of weight, it saved me from becoming a crisp after 10 hours under the Pyrenean sun.

Footwear: absolutely critical. Your feet will swell during the day, so shoes that are too tight become medieval torture devices by lunchtime. But if they’re too roomy you’ll find yourself sliding forward on the descents, slamming your toes with every step.

what do you mean we have to go!!!

Some days, water sources are scarce, so start hydrated and don’t wait until you’re seeing mirages. Around 1 pm, I routinely imagine a frosty glass of fizzy orange with ice cubes clinking and condensation running down the sides. The reality is a gulp of lukewarm water if I still have some and even that tastes pretty good.

As for socks—bring more than you think you need or at least always have a fresh pair to change into. And make them Merino wool. Anything else turns your feet into soggy blister bait. Once your skin goes soft, it’s all downhill. Once you know which socks will work with your shoes, you can chuck the rest away. (I guess this would’ve been a good exercise before I arrived ).

so worth it!

Distance is on a different scale here. Back home, 4.5 km around Centennial Park is a pleasant morning jog. In the Pyrenees, 4 km can take two hours of scrambling, climbing, sliding. And let’s not forget the weight: 12 kg on your back is considered a light day If you’re carrying a tent. Throw in two days of food and over a litre of water, and suddenly you’re a not-very-cold fridge climbing a mountain.

This hike is not for the faint-hearted but if you can survive the first week, your body adjusts, your mind toughens, and you start to appreciate the spectacular views.

At the end of the second stage and there’s no place I would rather be.

To be continued ……