Guinea-Conakry, Sierra Leone & Liberia

/guinea-conakry border

The principal border crossing between Guinea-Bissau and Guinea-Conakry lies at Buruntuma (Guinea-Bissau) / Koundara (Guinea), the easternmost practical exit point from Bissau territory and judging by local opinion, the only one that exists in more than cartographic theory. Although maps suggest alternative crossings farther south and closer to the coast, reports of overgrown jungle tracks—some barely wide enough for motorbikes—and a necessary, but long-submerged one-vehicle ferry, persuaded us inland.

Exiting Guinea-Bissau was swift and uncomplicated. The drive through the strip of no-man’s-land that followed was less reassuring, offering an early hint of the conditions ahead. On the Guinean side, the border post outside Koundara consisted of little more than a handful of thatched huts and two slightly sturdier buildings serving as Passport Control and Customs. Apart from four officials presiding over proceedings, the place was deserted and were it not for a protracted discussion over whether Birkenstocks qualified as flip-flops, the process would have been admirably efficient.

Victorious on the footwear question—although somewhat baffled by the official emphasis on road-safety advice—we crossed into Guinea-Conakry proper. What followed was a punishing drive over an unbroken expanse of ruts, craters, and loose rock, a surface that appeared to have been designed less for vehicles than for testing personal resolve. Progress toward Koundara town, and the now eagerly anticipated return of potholed tarmac, slowed to a crawl before grinding to a complete halt.

While edging through an especially brutal stretch, Bob’s rear suspension emitted an ominous groan, followed by a rhythmic clunk from the rear passenger side – the automotive equivalent of a polite cough before collapse. We pulled over to investigate. The flat tyre was obvious and were it not for the fact that we no longer had the locking nut key for the spare, not a big deal. More troubling, was the cause: a displaced suspension coil spring.

bush repairs preferred tool - a hammer

The uncomfortable pause when your world stops and seems reluctant to begin again doesn’t last long in Africa. Within ten minutes we were surrounded by twenty or so children, joined shortly after by a few older boys on motorcycles. We were only 13 kilometres from Koundara, so Ian climbed onto the back of one of the bikes to find a mechanic and departed which left me in charge of crowd control.

thisi s what happens if you lose the locking nut key

Never having had any desire to have my own children, I now found myself well outside my comfort zone. It was hard to remember the last time I’d made a paper aeroplane, and without internet coverage to help, progress was embarrassing. But I did learn something, just handing out coloured squares of paper was greeted with glee and much excitement, suggesting that novelty, like entertainment, is largely a matter of context. An hour later, Ian returned with the mechanic, who had come well prepared — with a hammer. In many bush repair situations the hammer has no doubt proved its worth but, as our socket wrench was the wrong size, the mechanic soon disappeared back to town in search of another tool, leaving us to reflect that roadside repairs, like border crossings, proceed according to their own timetable.

With Ian now on aeroplane production and, with the addition of a hopscotch grid scratched into the sand, another hour passed. On his return, the mechanic removed the flat and reverting to his preferred methodology, smashed the locking nut off the spare. Unfortunately, attempts to force the displaced suspension spring back into position failed, and he vanished once again in search of a third tool.

making paper aeroplanes

By now we were running out of ideas to occupy the children. Circles were drawn in the sand as landing targets for the paper planes, but not everyone had one, which quickly led to disputes. Slaps and smacks were exchanged with enthusiasm and the hopscotch grid dissolved under the scuffles. In the midst of this chaos, an older man appeared — quite literally from nowhere - and immediately set about attacking the spring by forcing an assortment of metal pieces between the coils. Unbelievably, an hour later the main spring was back in place. The inner helper spring, however, had lost its cap and remained defiantly out of position.

The spare wheel was fitted — despite being a different size, a detail no one felt the need to explain — money was distributed to everyone involved, and we set off again, even more slowly than before. The constant banging of the loose inner coil against the underside of Bob was deeply unnerving, but we limped into Koundara to find a festival in full swing and every room occupied. That night we slept on the forecourt of a petrol station, returning to the mechanic early the next morning with the aim of removing the inner spring altogether.

Six hours later — following a sheared shock nut and visits to both the local blacksmith and welder — the helper spring was finally out. Bob was driveable again, if far from healthy. To be safe, we bought another tyre, ignoring both the state of the tread and the fact that it was, yet again, a different size, and pressed on towards Labé.

wild night out

It is hard to imagine why anyone would visit Labé unless drawn by the prospect of a night at the local disco. The town was hectic and dirty, with roads that consisted largely of dumped piles of rock where any attempt at levelling had failed spectacularly. But after two days standing in the heat watching Bob on the receiving end of a hammer, we needed a break. Just outside town we found some relatively new accommodation with its own generator and solar panels. Hot water and round-the-clock electricity felt like extravagances after many days without either.

is this really a road?

The Labé region lies in north-central Guinea atop the Fouta Djallon plateau, around 1,050 metres above sea level. Often referred to as the “Water Tower of West Africa”, it is the source of several major international rivers, including the Niger, Senegal, and Gambia. Although it is theoretically possible to visit the region’s many waterfalls independently, the lack of marked trails has created a thriving niche for one well-known local guide, whose work supports not only his nine children but much of his wider community.

hassan bah village compound

Hassan Bah, a diminutive 63-year-old from the Fulani (Peul) ethnic group — one of Guinea’s largest, predominantly Muslim communities — welcomed us warmly into his village compound. Within minutes he had produced a flask of lemongrass tea sweetened with local honey. With boundless energy and obvious affection for his highland home, Hassan and his nephew guided us on a series of hikes, imaginatively named Wet and Wild, Chutes and Ladders, and Indiana Jones.

A small but steady trickle of overlanders passed through during our stay, including a couple from New Zealand who had begun their journey with a UK-based overland trucking company driving from Morocco to South Africa. Their trip had started with two troop-carrying trucks, each carrying fourteen people. One of the trucks, driven by a distracted septuagenarian had, just days before, lost an argument with a tree and two passengers were killed.

Unsurprisingly, the group was badly shaken, made worse by the fact that twenty-four people were now crammed into a single truck after four sensibly opted to return home. Uncomfortable with how things were unfolding, our new friends had hired a local guide and were exploring independently before rejoining the truck in Ghana. Hearing their story — and reflecting on our own recent misfortunes — it was clear that things could have been much worse.

Leaving Hassan’s was difficult, the prospect of tackling treacherous roads with compromised suspension weighed heavily and, against our better judgement we followed his advice and opted for the shorter route toward the Sierra Leone border. It took three days to reach it. Rough, dusty mountain tracks rarely allowed speeds over 20 kph and when we eventually reached tarmac, we sat for hours in the gridlocked traffic around Conakry, progress measured largely in patience.

We pressed on to the border and, for the briefest of moments, our luck appeared to have changed. We were processed swiftly out of one country and into the next and had just begun to congratulate ourselves on our growing fluency in West African bureaucracy when ……

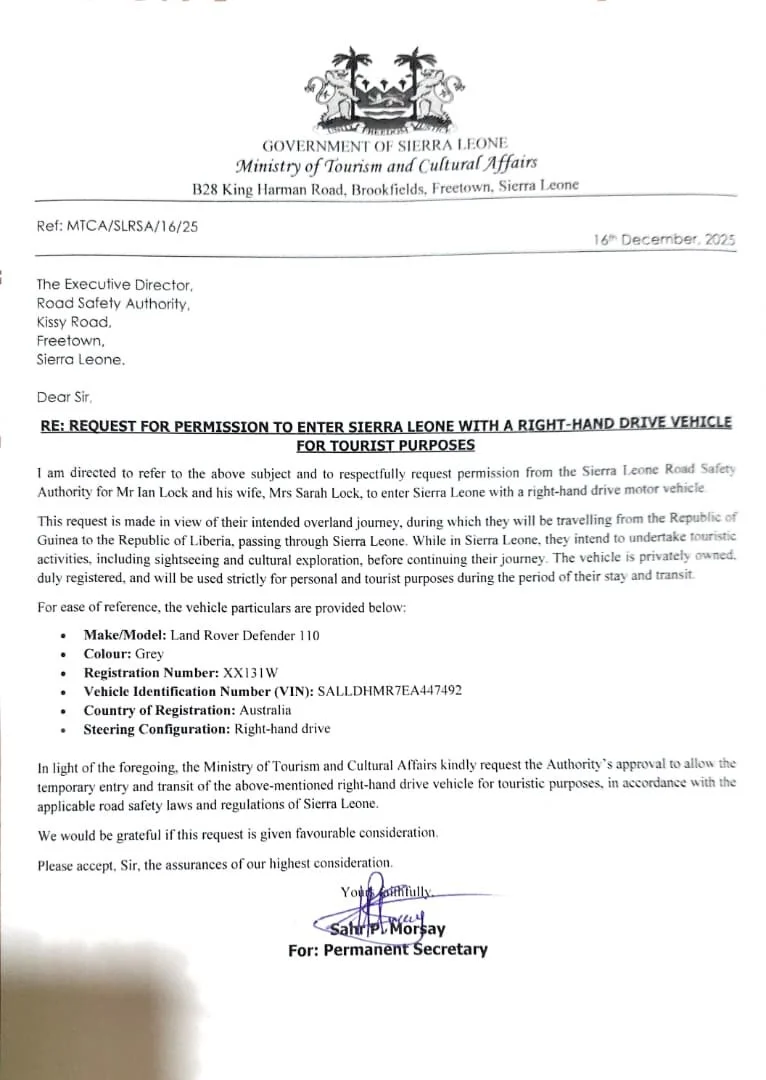

…… we were halted in front of the by now all-too-familiar, rope barrier. Western Africa has a habit of presenting a fresh challenge just as you start to feel competent. This time it was the Road Safety Corps. We knew from iOverlander that, as in Guinea-Conakry, we would be paying road tax. Handing over 40 Euro wasn’t the issue. The problem was that Sierra Leone had banned the importation and use of right-hand-drive vehicles.

The justification, we were told, was that research linking them to higher accident rates. As this was being explained, a procession of clapped-out vehicles rattled past, belching thick black toxic clouds of smoke. Scooters carried four to six people at a time, while community minibuses were barely visible beneath layers of passengers clinging to the outside and perched on towering roof loads. But experience had taught us there was no value in debating logic. It was far better to focus on finding a solution.

What followed offered more insight into the inner workings of Sierra Leone’s ministries than we ever knew we needed - or wanted. The Ministry of Land Transport, Ministry of Tourism, the British Embassy, and the Station Chief of the Road Safety Corps were all contacted. As we sat beneath a sign reading “Welcome to Sierra Leone”, Ian made over 120 phone calls while twenty-four hours quietly slipped by, before the Station Chief finally arrived, apparently keen to join the spectacle.

safer than a right hand drive?

Hope was fading and the prospect of a lengthy detour loomed when, suddenly, a letter appeared on the Chief’s WhatsApp. Permission to transit had been granted. At last, we were allowed to enter.

Set on the western edge of Africa and bordered by Guinea and Liberia, Sierra Leona is still recovering from one of the continent’s most brutal civil wars. Between 1991 and 2002, the country was ravaged by a conflict marked by widespread atrocities, including the forced use of child soldiers by both rebel groups and government forces. The war was largely fuelled by diamonds mined in conflict zones and exchanged for weapons; a trade later popularised by the Hollywood film Blood Diamond. More than two decades on, communities are rebuilding, but the country remains deeply divided and hampered by corruption.

freetown

free camping en-route to liberia

Once over the lowered rope and leaving the border nonsense behind, we headed straight for Freetown, a capital founded in the late 18th century by British abolitionists. Its early settlers included the Black Poor of London, later joined by Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia and Jamaica. While the settlement provided a home for freed and formerly enslaved Africans, it also established a British colony that primarily served imperial interests. Driving into the city, the layers of history were unmistakable: colonial buildings in various states of decay, street names like Freedom Way and Independence Drive hinting at past aspirations, and a port that still anchors the economy.

The economy reflects both Sierra Leone’s natural wealth and its fragility. Diamonds, bauxite, and iron ore remain central, alongside agriculture, which employs most of the population through small-scale farming of rice, cassava, and cocoa. Much activity operates informally, shaped by fluctuating commodity prices, weak infrastructure, and periodic shocks such as Ebola and COVID-19. Growth exists, but it is uneven and easily disrupted, making daily life highly adaptive rather than predictable.

It was crowded, noisy, and exhausting – but unavoidable. We needed to visit three embassies to secure visas for Liberia, Ghana, and Côte d’Ivoire, and Bob was optimistically hoping that a tyre and several replacement parts would be arriving from the UK.

A handful of UK-based companies specialise in shipping Land Rover parts worldwide. Import taxes and customs duties are paid in advance, removing much of the uncertainty — and delay — that often accompanies international freight. We had been tracking our parts for days, hoping they and we would arrive in Freetown at roughly the same time. Remarkably, this is exactly what happened despite the parts taking a route that suggested an enthusiasm for sightseeing. They travelled first to Nigeria, then Côte d’Ivoire, detoured through Liberia and finally landing in Sierra Leone, where they were delivered directly to a helpful and refreshingly impartial Toyota garage. Bob was repaired and, once again, ready to move.

cycling in lunsar

Before heading for the Liberian border, we stopped in Lunsar, visiting the local cycling club and spending a couple of days in a town that rarely sees tourists, let alone white ones. Our arrival was met with blank stares but as we waited outside a tin shed crammed with old bicycle parts, locals soon gathered and introductions gradually followed. By the time we left, it felt like we were saying goodbye to family and, through a bit of impromptu crowdfunding with friends back in Australia, we raised enough money for Sheik, a strong local cyclist, to relocate to pursue his cycling career overseas. Quick update - Sheik is flying to Dubai on 15th February and we wish him the best of luck.

This warmth and rapid inclusion is something we have experienced repeatedly since southern Senegal. Stepping briefly into other people’s communities, we have never felt judged and despite the hardships visible all around us, have been met with curiosity, generosity, and kindness. These moments have added a new dimension to our travels and provide a necessary counterweight to the inevitable frustrations of overland travel in this part of the world.

monrovia

Next up Monrovia, the capital of Liberia. After the excellent roads of Sierra Leone, we were suddenly back on pot-holed tarmac and - rather oddly - our slow progress was now being measured in miles rather than kilometres. This peculiarity owes itself to Liberia’s long-standing ties with the United States. Its founding history mirrors Freetown in some respects: established by the American Colonisation Society for freed slaves returning from the Americas, the nod to the US was evident in grid-like streets, American-style churches and holidays and a flag that could almost pass for a distant cousin.

crazy kehkeys

The city itself is sprawling yet scarred by more than a decade of civil war. Ruined and bullet-riddled buildings serve as a constant reminder that Liberia remains one of the 10 poorest countries in the world. The short bursts of relative wealth from rubber, timber and iron ore never translated into sustainable infrastructure. The evidence sits silently on Ducor Hotel, one of Africa’s first and most prestigious five-star hotels, which hosted Africa’s elite. Whether the anecdote about Idi Amin, former dictator of Uganda, swimming in the pool with his gun is true or apocryphal, it seems emblematic of the hotel’s storied - and slightly absurd - past.

Despite the city’s wide streets, we approached Monrovia at a snail’s pace. The traffic, which was about 90% kehkeys, appeared to operate on the principle of negotiation rather than regulation. Main roads were choked with market stalls, leaving barely enough space to inch forward through a chaotic jumble of thousands of people and the contents of what looked like container loads of used clothing, electronics, and household goods. We assumed most of it came from Europe, the US or Asia – but that theory quickly changed when a local guide walked by wearing a polo shirt emblazoned with St. Peter’s College, Adelaide.

Reaching our hotel unscathed was a small triumph, and we lingered for a few days. The long Embassy waits in Freetown combined with recent border hassles, had left us feeling wiped out and the slightly colonial vibe of the well-stocked hotel bar was very welcome.

mt nimba lodge

Monrovia itself - and Liberia in general – offers few conventional tourist sights. However, just before we reached the Ganta border into Cote d-Ivoire we spent a few days in the mountains of Nimba National Park.

Mt Nimba, once a mining area, has gradually greened over 45 years of disuse after operations ceased with the outbreak of civil war. The park has a remote lodge with accommodation and hiking opportunities and a large parking area for overlanders. It is also notable for its tri-point stone, marking the convergence of Guinea, Liberia and Cote d-Ivoire, a neat geographical full stop marking the end of our time in Liberia.